|

| University of California at Davis students reoccupy their campus's Quad Monday the way kids at a geek/ag school do, with high-level engineering |

|

| "No taxation without representation," here in a protest document signed by John Hancock. Sadly, only half the quote can be recalled by Republicans. |

Thus, one is a classic movement of the modern era, the Tea Party is a top down, wealth-financed movement which owes its strategies and techniques to the powerful political class - they even have their own cable television network in FoxNews. It is, of course, limited by national boundaries and has very traditional goals.

The other is of the contemporary world. Its television is LiveStream and UStream, its media is Twitter, Text-Messaging, and Blogs. Its strategies are ad hoc and constantly evolving. It has proven itself to be global almost overnight. And one more thing, which traditional politicians, leaders, even many educators fail to understand, it is non-specific about most goals because it is about democracy. It is a global pro-democracy effort, and naturally it terrifies the oligarchs, whether American, British, Russian, whatever.

Both groups have some connection to American roots. The Tea Party - and perhaps this works because of the memory issues of many Social Security and Medicare collecting adherents of the cause - bases its appeal in the first half of the four word slogan of the 1773 Boston Tea Party. It is stunningly amusing that this movement which now paralyzes most American government cannot recall all four words, although, to be fair, two of the four words have multiple syllables, so, ya know... but it is also horrifyingly sad that Americans know so little of even their own history.

The "Occupy Movement" comes, on the other hand, from something very deep in American history, and something universally appealing: true democracy, where the voices of all are heard and the needs of all are respected. There is much about the Occupy Movement, laughed at as it was when born from powerless unknowns two months ago as Occupy Wall Street, which links directly back to Ethan Allen's Green Mountain Boys, equally opposed to power from London, Albany/Kingston (New York's seat of government at the time) or Portsmouth/Exeter (New Hampshire's seat of government at the time), and to those who formed the Free Republic of Franklin in 1784, and maybe to those who made Woodstock the safest large city in the United States in 1969.

"The [Free Republic of Franklin] legislature made treaties with the Indian tribes in the area (with few exceptions, the most notable being the Chickamauga), opened courts, incorporated and annexed five new counties, and fixed taxes and officers' salaries. Barter was the economic system de jure, with anything in common use among the people allowed in payment to settle debts, including federal or foreign money, corn, tobacco, apple brandy, and skins ([The Governor] was often paid in deer hides)."This is a global, a universal, a human idea. Unlike the Tea Party's commitment to selfishness - "I don't want to pay for anything anyone else may receive." - the Occupy Movement is based in basic humanity, we all deserve opportunity, we all deserve to be included in society, we all deserve to be heard. And this is a radical re-understanding of democracy, because, though the roots of this run deep in early America, it is not what we've taught in school the past 150 years, where the concept that "majority rule" = "democracy" has taken charge, along with the idea that "democracy" = "you get to vote occasionally."

|

| When Norman Rockwell described "Freedom of Speech" as one of the Four Freedoms we fought WWII for, he used the Occupy Movement's "General Assembly" as the model. |

The Occupy Movement is not a counterpart to the Tea Party notion of selfishness and our society doing less for each other, rather, it is call for a fundamental rethinking of what democracy is, and what priorities we, as a society should have. No wonder it scares Democrats in Washington almost as much as Republicans.

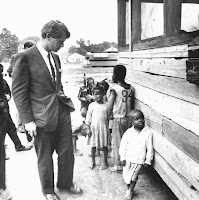

Which brings us to Davis, California...

On a couple of autumn days when we would expect university students to be focused on (a) football and (b) getting home for Thanksgiving. After all, when we last looked at an American university campus we were watching Penn State students riot because a football coach had been fired for covering up child sexual abuse for a decade, while allowing that to continue. So Davis took us by surprise, but it also revealed a series of key questions we must be asking in our schools... in every one of our schools.

How does this happen? I am not advocating for removing personal responsibility, I agree with the United States government position from Andersonville to Nuremberg to My Lai, your orders are secondary to your humanity, and yet... as in all of those cases, the question is rarely a clean one.

I encourage you to watch the video above with your students, and also watch The Andersonville Trial

This is a question which defines us, and though - thankfully - rarely as dramatically as in the case of Lt. Pike, it is a question which controls the course of our lives.

Two: Where were the educators? When UCD education professor Cynthia Carter Ching wrote her open letter to Davis students and faculty she apologized to the students, "You know, it wasn’t malicious. We thought it would be fine, better even. We’d handle the teaching and the research, and we’d have administrators in charge of administrative things. But it’s not fine. It’s so completely not fine. There’s a sickening sort of clarity that comes from seeing, on the chemically burned faces of our students, how obviously it’s not fine. So, to all of you, my students, I’m so sorry. I’m sorry we didn’t protect you. And I’m sorry we left the wrong people in charge."

The fact is, we've become so institutionalized in so many places, that we, in education, forget what our purpose is, and as Ching says, "It's not fine."

I suggested on Twitter yesterday, "Dear University Presidents, if you find students "occupying" their own campus, sit down with them and be an educator

So, this is a time to listen to your students. To, yes, shut up and listen. Let them record their day with the video cameras on their phones, or give them flip cameras. Let them show you what "you" - their school - is teaching. And then, truly respond to that.

Three: What does democracy mean? I remember that my father, discussing the aftermath of the World War II in which he had been a central combatant, told me that, "We all fought for the Four Freedoms, but afterwards, the U.S. decided to only worry about two, and the Russians decided to only worry about two." Once again, the inability to remember four - must be a lesson here.

My father meant that while the U.S. focused on Freedom of Speech and Freedom of Religion, the Soviet Union focused on Freedom from Want (jobs, food, housing, health care, education for all) and Freedom for Fear (a huge border area of nations controlled to make sure that the Germans did not come back). He wasn't making excuses for either, he was faulting both.

For my father, the reason he had fought his way through the nightmares at Metz and Bastogne and Dachau, and had crossed Germany to end up in Plzen, was to assure people's rights, from America to Prague, to all four. He felt badly cheated.

I've talked about experimenting with different forms of voting before, letting our students learn options and ask questions, but this needs to go beyond that. What are the purposes of our society? What should we do together? What things are all of our responsibility? What is government supposed to be? How are decisions made? What are the rights we should all have? What are the responsibilities we should all have?

You cannot limit this to the United States or whatever nation you are in, you need to allow students the range of options contemporary societies have chosen, from French right to health care and education to the Finnish right to broadband to the East German right to long family vacations at the beach.

Democracy deserves better than a short answer. The Occupy Movement understands that, and we, with our students, need to start asking the same questions.

Happy Thanksgiving to all in the United States, and welcome to Advent to all.

- Ira Socol