The

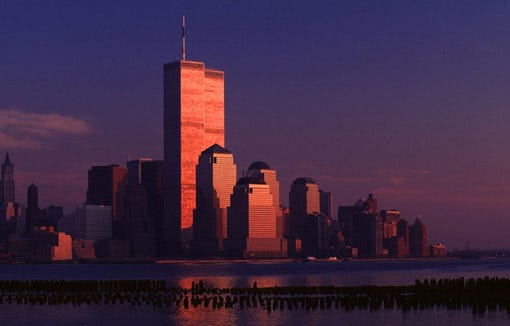

World Trade Center, as it existed, say 1970 to 2001, was truly one of

my favorite places on earth. Others I know describe it as “ugly” or

“blocky,” or, in the language of The Atlantic or The New York Times, “anti-urban,” but they’ll never convince me.

I

watched it most days for many years, key years for me, childhood,

adolescence and young adulthood. Somehow, is it possible? I have a

memory of my father, New York World Telegram & Sun

in his hands, reading to me about how people feared that the television

signals from the Empire State Building would get scrambled when they

echoed off these not yet built super towers.

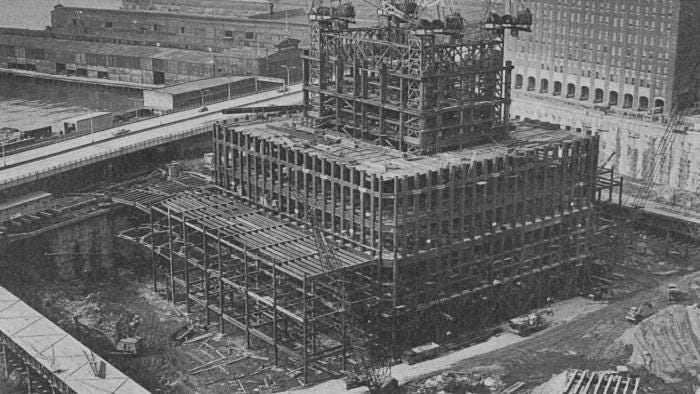

I remember a fascination with the ‘seawall on land’ — what I understood the slurry wall

to be, with the ‘straw within a straw’ framing system, with those

massive exterior trusses, with the whole giant platform underground…

So

I watched it rise. Maybe it was, for me, a symbol of ‘my city,’ new and

challenging all the old. The elegant brick skyscrapers we’d inherited,

the Empire State, the Chrysler Building, Rockefeller Center, Daily

News Building, the Wall Street towers — the Bank of the Manhattan Company Building,* Cities Service Building, One Wall Street

— were the work of my father’s childhood, and his generation were

justifiably proud. The sleek postwar creations, Levert House, the

Seagram’s Building, Chase Manhattan Plaza, were also that generation’s

work — part of their triumph in the war and domination of the world.

Buildings like the United Nations, the reclad/rebuilt Allied Chemical Tower, the GM Building seemed to belong to the real baby boomers, our older siblings and cousins who grew up with moms at home.

The World Trade Center, though, was all ours.

It

was huge and aggressive and incomprehensible in scale. As it began to

be clad in curtain wall it was also postmodern before any of us knew the

word, it’s tracery owing more to the Woolworth Building — that tower

displaced in the city’s heart by the structures of our parents’

childhood — than to anything since. It became changeable across the

changing light of the day, it wasn’t a solid solid.

Maybe most importantly, it was a beacon, calling us back to the city so much of the previous generation had fled.

And

when built it was an enormous playground, from the mall — ahh to hang

out watching the 6 pm human waterfall at PATH Square — to the plaza, to Windows on the World, where faux sophistication and the greatest views ever could be had for the cost of an overpriced drink.

OK then. Nostalgia.

History

is cruel and my father’s landmarks stand and mine is gone. And my

response to that loss was typical: rebuild it as it was, stop calling it

‘the twin towers’ or ‘north tower’ (to know it was to say “Trade

Center” and “One” or “Two”), put the same restaurant back on top…

Nostalgia

of course leads to the rejection of the new — an almost unconscious

anger toward the world moving on. But cities are dynamic for reasons

good and bad. Like many things…

I

am glad that my son knew the Trade Center that was. I am glad he looked

out from up top and looked up those staggering aluminum clad sides…

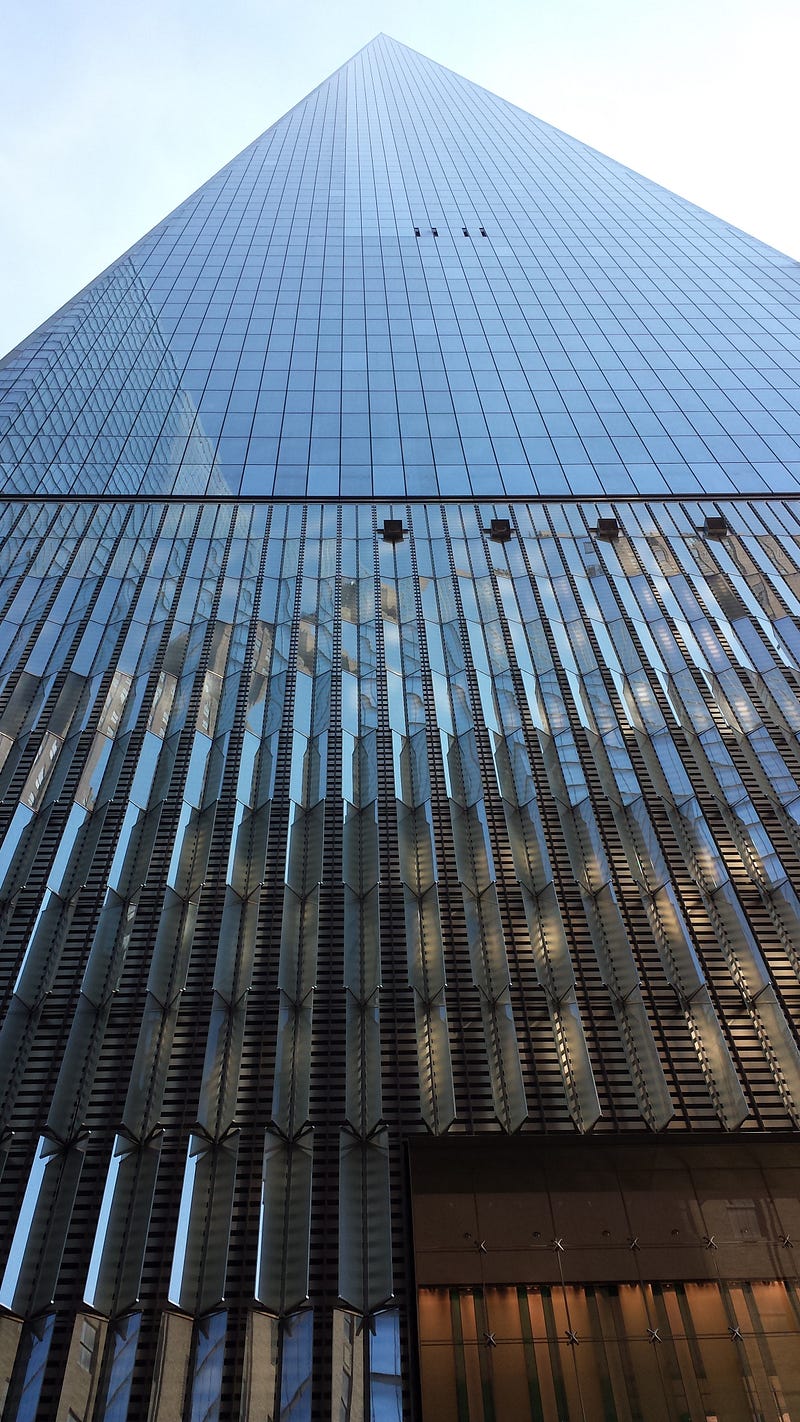

…but

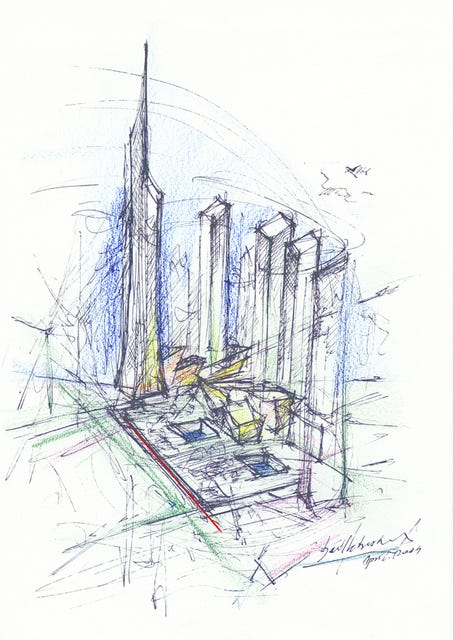

now my kid has taught me to love the new One World Trade Center, to

enjoy the park, to marvel at the complexity of the new design. And he

taught me that with just a few simple statements that made me look anew.

He

started simply by saying that the new One World Trade Center — then

just a forming skeleton — ”wasn’t bad. It would be a great building in

another place, maybe Houston.” And with that I looked at the shape

again, trying to put my generalized disdain for architects Skidmore Owings Merrill to bed for a moment.

Next,

glass walls in place, he encouraged me to stand near the phone company

building and look up. And I did, and found myself enthralled.

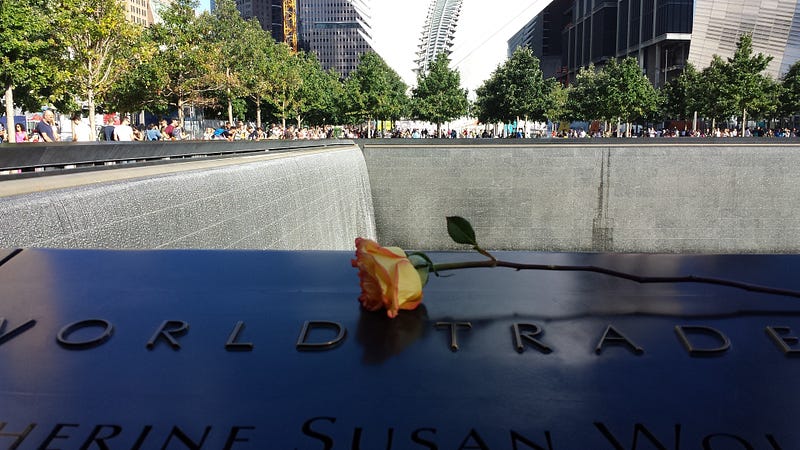

Once

here, at the magical infinite tower, I could begin to find all the

rest. I could start to see the wheel of towers — the not-quite-lost

magnificence of Daniel Libeskind’s plan —

emerging around the park and the great lost dinosaur skeleton on

Santiago Calatrava’s train station. I could see the memorial

park — assuming the morbid museum will be forgotten — becoming the kind

of gentle green spot downtown has needed so much more of. (The true success of a memorial can only be measured after all who remember the actual event have gone.)

A parable, of course.

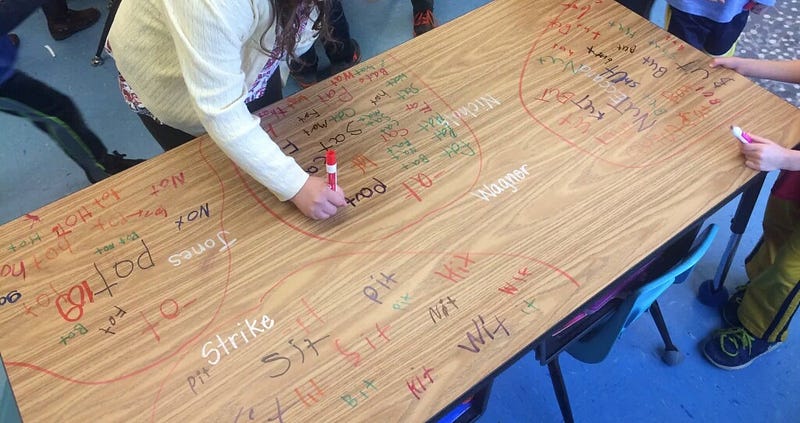

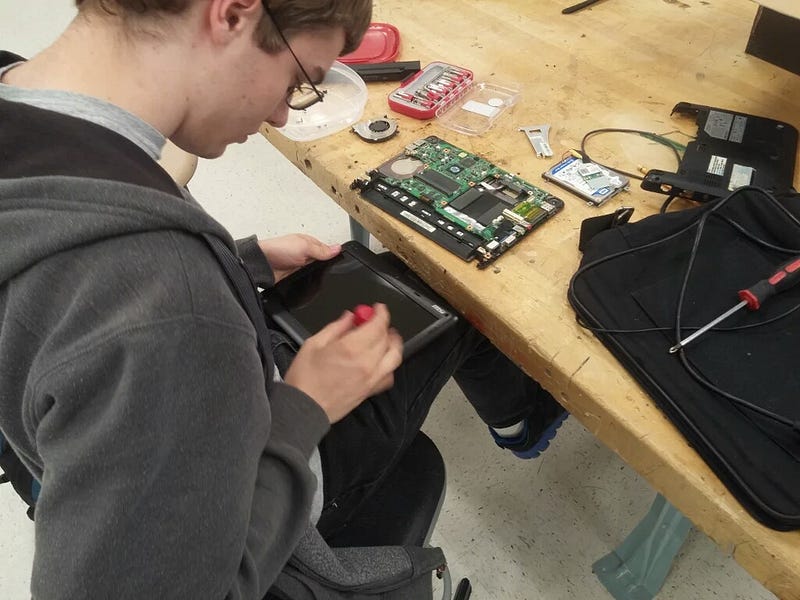

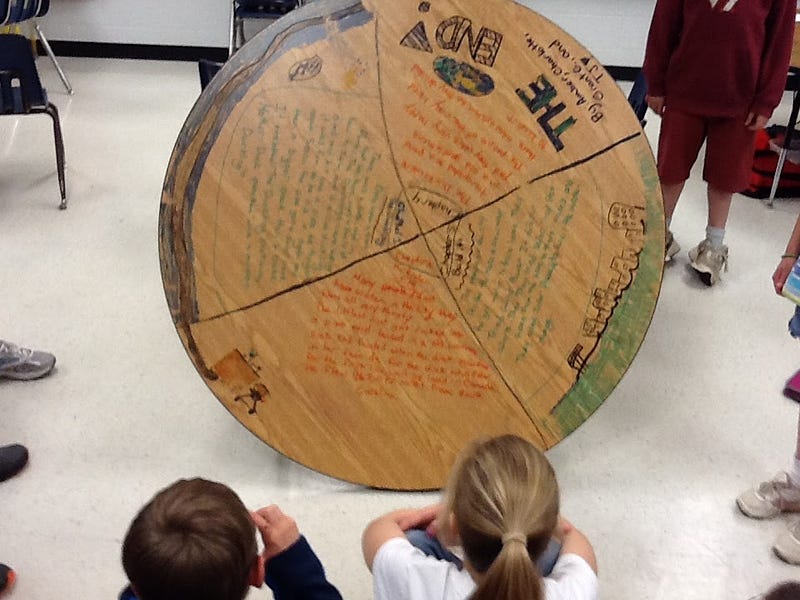

There

are so many levels of learning science here. From my passion for the

gigantic statement of a new day I learned history, I learned the science

of construction, I found a love of math in the structure. I began an

understanding of semiotics — the signs and symbols that create cultural

comprehension — that has stayed with me for life. I learned the choices

of urban spaces and the patterns of city movement.

Imagine what I might have learned if the schools I attended had supported passion-based learning.

From its destruction I learned something much more deeply about those symbols, but that’s another story.

And

from my conversion on the new building, my shift from calling it “a bad

Houston skyscraper,” the slow acceptance of the loss of both the

original buildings and the loss of the pure artistry of Libeskind’s vision, I learned about my own struggles with the impact of change.

So

much of what continues to haunt education rides on the back of cultural

remembrance and image preservation. It begins, all too often with

teachers teaching as they were taught. And it ends with the preservation

of crap like hall passes and bells ringing, late slips and petty rules,

because, “we’ve always had them,” and, “we don’t want to change

everything right away.”

But

you know… sometimes you do. I have friends who will bemoan the loss of

the ‘Radio Row’ neighborhood to the first World Trade Center. But the

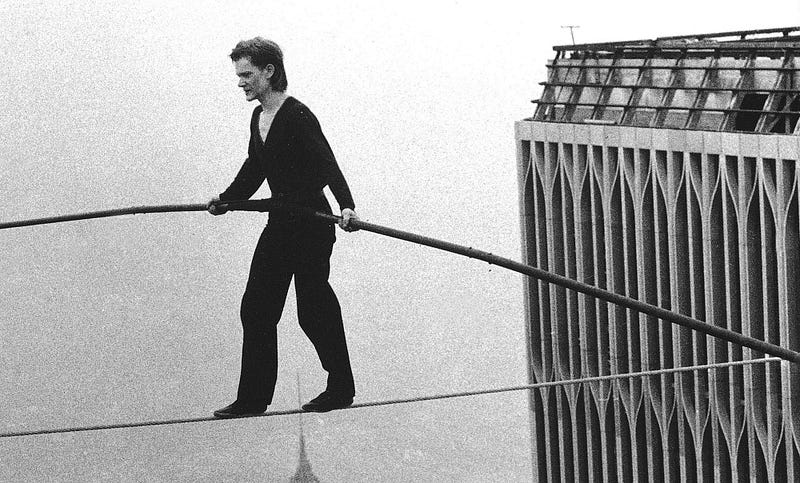

towers rose and Philippe Petit made them instantly a part of the rich

fabric of the city. They were beacons in a dark time.

The

loss of that complex was an incalculable tragedy, but, in its wake is a

new city with new aspirations and perhaps much higher goals.

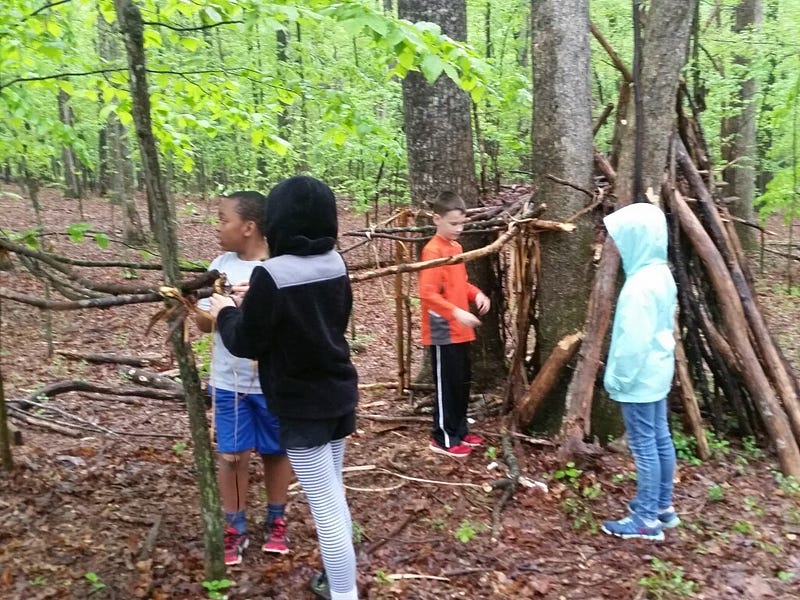

We

were not born to live in the past. And if we are educators we simply

cannot afford to live even in the present. The future is our children’s

time, and we must be brave enough, every day, to help to take them

there.

- Ira Socol